So finally, the Ancient Mariner has seen land, and a small boat is rowing out to save him, with a hermit on it. Let’s get stuck into the final part:

PART THE SEVENTH.

This Hermit good lives in that wood

Which slopes down to the sea.

How loudly his sweet voice he rears!

He loves to talk with marineres

That come from a far countree.

He kneels at morn and noon and eve—

He hath a cushion plump:

It is the moss that wholly hides

The rotted old oak-stump.

So firstly, that’s a weird kind of hermit – a loud and sociable one! But it’s established that he’s a holy man who lives a simple life: the ‘cushion’ he kneels on for prayer is a moss-covered tree stump. Of course, the Mariner wouldn’t have known this detail about the hermit at the time, he must have learned it since – but telling the wedding guest about the goodness of his saviour is obviously, for the Mariner, a key beat in the story.

The skiff-boat neared: I heard them talk, "Why this is strange, I trow! Where are those lights so many and fair, That signal made but now?" "Strange, by my faith!" the Hermit said— "And they answered not our cheer! The planks looked warped! and see those sails, How thin they are and sere! I never saw aught like to them, Unless perchance it were "Brown skeletons of leaves that lag My forest-brook along; When the ivy-tod is heavy with snow, And the owlet whoops to the wolf below, That eats the she-wolf's young." "Dear Lord! it hath a fiendish look— (The Pilot made reply) I am a-feared"—"Push on, push on!" Said the Hermit cheerily.

The angelic spirits that attracted their attention have left the ship now, and all that’s left is ‘warped’. The hermit’s description of the sails is incredibly detailed and evocative – they are like the skeletons of leaves that still cling to the trees in winter when the owlet (a young owl) whoops to the wolf below ‘that eats the she-wolf’s young’. I had to google whether the owlet could eat the she-wolf’s young, but apparently no it couldn’t. However wolves can eat their own, though they don’t tend to kill them. Perhaps the cubs have died of cold or hunger? It’s a very bleak image either way: a predator calling down to another predator; a wolf gnawing on a wolf cub. It suggests a kind of godlessness. The hermit seems to sense that the ruin of the ship comes from a place of evil. And the pilot picks up on this too – it looks like a boat out of hell. ‘Fiendish’.

The boat came closer to the ship, But I nor spake nor stirred; The boat came close beneath the ship, And straight a sound was heard. Under the water it rumbled on, Still louder and more dread: It reached the ship, it split the bay; The ship went down like lead. Stunned by that loud and dreadful sound, Which sky and ocean smote, Like one that hath been seven days drowned My body lay afloat; But swift as dreams, myself I found Within the Pilot's boat.

The mariner is, again, weirdly passive in this. There is no sense of his terror as the ship sinks – instead he somehow floats like a corpse. As if he in fact is dead and has been for seven days. Does this make more sense of the poem? Let’s remember Coleridge’s brother Frank, the sailor who killed himself. What if the arbitrary killing of the albatross was actually a metaphor for suicide: for that irrational, random act of soul-murder and self-harm? We could read everything that comes after as a kind of purgatory – from the verb purgo: to clean – where he has to undergo purifying punishment before being allowed back to God.

Also, Frank was hallucinating when he killed himself, and clearly very sick. Perhaps the whole voyage has been a terrifying hallucination, and the Mariner looks dead now because he is mortally ill?

Upon the whirl, where sank the ship, The boat spun round and round; And all was still, save that the hill Was telling of the sound. I moved my lips—the Pilot shrieked And fell down in a fit; The holy Hermit raised his eyes, And prayed where he did sit. I took the oars: the Pilot's boy, Who now doth crazy go, Laughed loud and long, and all the while His eyes went to and fro. "Ha! ha!" quoth he, "full plain I see, The Devil knows how to row."

The hermit and Pilot are terrified when he moves his lips, because they were sure he was dead. Now he – the Mariner – has become the zombie; the undead; Life-in-Death. The Mariner taking the oars is also understandably alarming. He has been so passive throughout the poem, this is a moment of him seizing his own destiny. But it must also look – to those on the boat – like the zombie has commandeered their vessel. The pilot’s boy laughs hysterically: he thinks the Mariner is ‘fiendish’ like the ship, perhaps even the devil himself.

And now, all in my own countree, I stood on the firm land! The Hermit stepped forth from the boat, And scarcely he could stand. "O shrieve me, shrieve me, holy man!" The Hermit crossed his brow. "Say quick," quoth he, "I bid thee say— What manner of man art thou?" Forthwith this frame of mine was wrenched With a woeful agony, Which forced me to begin my tale; And then it left me free. Since then, at an uncertain hour, That agony returns; And till my ghastly tale is told, This heart within me burns. I pass, like night, from land to land; I have strange power of speech; That moment that his face I see, I know the man that must hear me: To him my tale I teach.

This is a great passage. We might any of us be asked ‘what manner of man art thou?’ But few humans actually have a spirit inside them that is angelic or demonic. Instead, for most of us, it’s complicated. It’s a long story. To really connect with any human being, you have to hear their story.

We mentioned earlier that this idea of being cursed to repeat a story is a horror trope. But it’s also a trope which writers can sympathise with. Many of us feel, after all, that we write because we must. We are compelled. The Mariner, here, is a stand-in for Coleridge, who also – interestingly – spent his life returning to this poem, glossing it, redrafting it: cursed himself to retell it over and over.

It might make us think about audience too. The Mariner doesn’t tell his story to everyone. Only a few are chosen, because they need to hear it. The implication is that we, the reader, have somehow been singled out by fate to hear this poem, because we must be taught its lesson.

What loud uproar bursts from that door! The wedding-guests are there: But in the garden-bower the bride And bride-maids singing are: And hark the little vesper bell, Which biddeth me to prayer! O Wedding-Guest! this soul hath been Alone on a wide wide sea: So lonely 'twas, that God himself Scarce seemed there to be. O sweeter than the marriage-feast, 'Tis sweeter far to me, To walk together to the kirk With a goodly company!— To walk together to the kirk, And all together pray, While each to his great Father bends, Old men, and babes, and loving friends, And youths and maidens gay!

…And we’re back at the wedding. The ceremony is over, people are cheering. There is bustle; bells and song. And the Mariner gushes like Scrooge on Christmas morning: this is life. The little church, friends, old men, babies, young people, all of life! Now he has told his story, you can actually feel the burden has lifted from him.

Farewell, farewell! but this I tell To thee, thou Wedding-Guest! He prayeth well, who loveth well Both man and bird and beast. He prayeth best, who loveth best All things both great and small; For the dear God who loveth us He made and loveth all.

And here is the environmental message Coleridge eventually settles on as his moral – so ahead of its time. Loving ‘man and bird and beast’ equally is itself a kind of prayer. It is a beautiful, simple message to pass on, even if the story we have just heard might strike us as communicating something far more complicated than this.

And can I hear the hymn ‘All Things Bright and Beautiful’ in there? It was written in 1848 by Cecil Frances Alexander, but surely she would have known the Coleridge poem? The Ancient Mariner’s strange influence ripples through so many things…

The Mariner, whose eye is bright, Whose beard with age is hoar, Is gone: and now the Wedding-Guest Turned from the bridegroom's door. He went like one that hath been stunned, And is of sense forlorn: A sadder and a wiser man, He rose the morrow morn.

We return to the ice in this final image: the ‘rime’; the ‘hoar’. And the Wedding-Guest? If he is a stand-in for the reader it is interesting that he is left ‘stunned’ and ‘forlorn’. Surely the Mariner’s enthusiasm for the human company at the kirk should leave the guest feeling blessed? Surely his moral about treating birds and beasts with respect should leave us inspired? Why are we left, instead, ‘sadder’?

It feels like Coleridge is voicing his own emotions at the end. Writing this poem has made him a better poet, but it has also left him feeling uneasy and dazed. He has tried to impose a moral on it, but he still doesn’t really know what it is all about. It is some laudanum-and-grief-fuelled living-nightmare. It has possessed him. It has punished him. It has loosed a new darkness into literature.

I cannot help but think of Kafka here: ‘What we need are books that hit us like a most painful misfortune, like the death of someone we loved more than we love ourselves, that make us feel as though we had been banished to the woods, far from any human presence, like a suicide. A book must be the axe for the frozen sea within us’.

For all its flaws, ‘The Rime of the Ancient Mariner’ is such an axe.

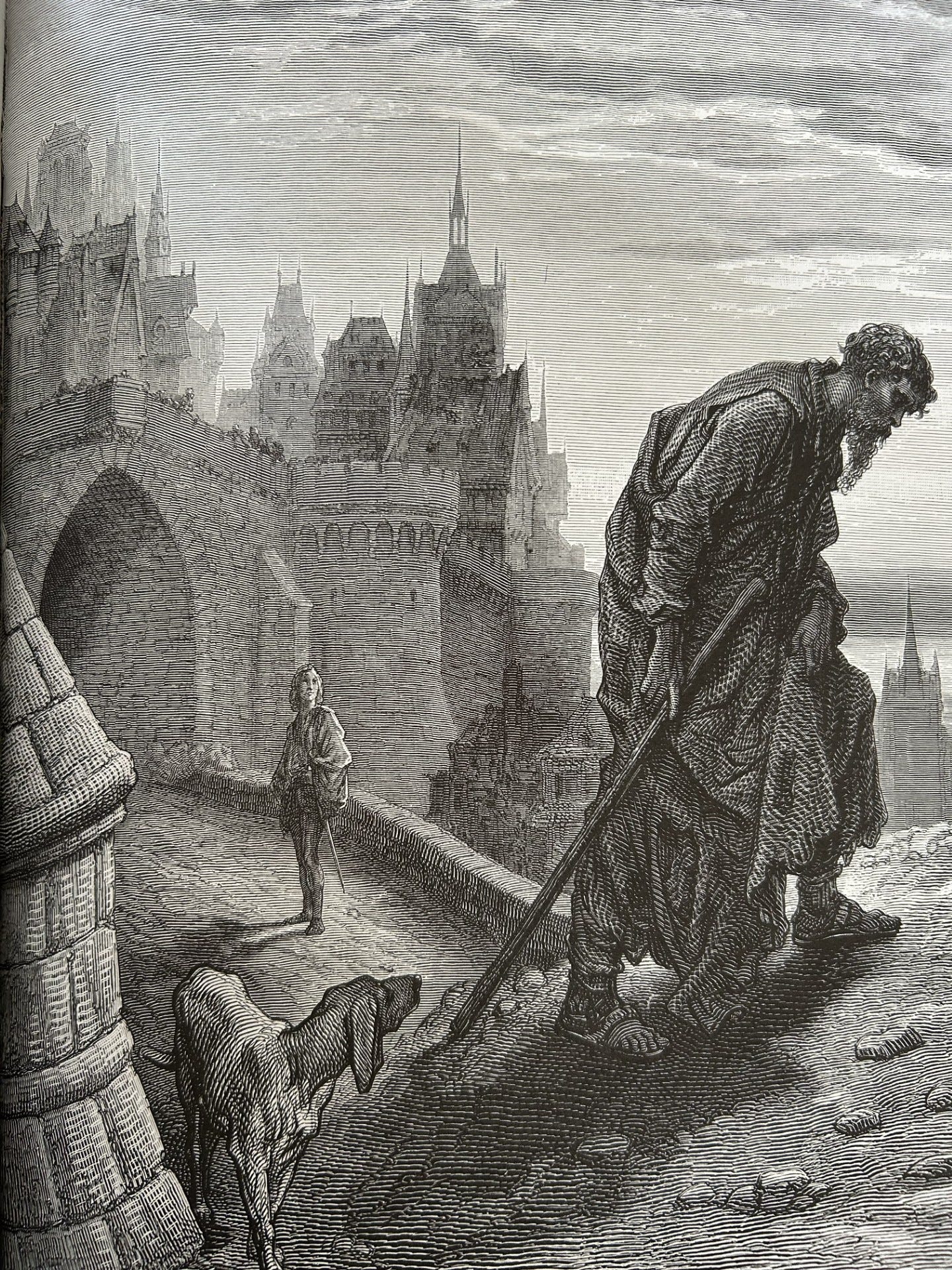

(final image by Gustave Doré)