(The Sin by Franz Stuck, showing Eve and the serpent)

So we’re up to the second section of Keats’ Lamia now. Luckily for me, it’s a bit shorter than part one, but I think if I’m going to get this finished before the Christmas break, I’m going to need to rattle out two posts this week (the last one reached Substack’s word limit)! Hope that’s okay with everyone. Part two begins with these brilliant lines:

Love in a hut, with water and a crust,

Is—Love, forgive us!—cinders, ashes, dust;

Love in a palace is perhaps at last

More grievous torment than a hermit's fast—

That is a doubtful tale from faery land,

Hard for the non-elect to understand.

This is wonderful isn’t it? Such a brutal truth: that far from love being all you need, without the basics needed to sustain life, love can mean very little. And Keats’ aside there ‘Love, forgive us!’ is both funny and sad: perhaps when it is when we are starving and suffering we need love most, though we may least appreciate it then.

And then there is the other truth: that love in a palace can also be a torment – or so the fairytales would have us believe. (Though being non-elect, like us, Keats admits it is hard to imagine).

Had Lycius liv'd to hand his story down,

He might have given the moral a fresh frown,

Or clench'd it quite: but too short was their bliss

To breed distrust and hate, that make the soft voice hiss.

Besides, there, nightly, with terrific glare,

Love, jealous grown of so complete a pair,

Hover'd and buzz'd his wings, with fearful roar,

Above the lintel of their chamber door,

And down the passage cast a glow upon the floor.

‘He might have given the moral a fresh frown’ is a phrase that absolutely clunks to me. I know this was written long ago, but it sounds like a thing that nobody would ever say unless they’d been fruitlessly seeking a rhyme for ‘down’ for ten minutes. (If you find yourself in this situation - which is common in English-language poetry as there are such a limited number of rhyme pairs and sometimes it isn’t appropriate to drown or crown anyone, or introduce a clown, or note that something is brown - the thing is to try swapping ‘down’ for another word, eg: ‘hand this story on’).

Anyway, I think Keats is saying that, although lovers who live in palaces often end up hating each-other, these two haven’t had time (some days seem to have elapsed since part one, but not that many).

Very intriguingly Love – who Keats personified in the last few lines by directly addressing him – has here become a full character, who is jealous of Lycius and Lamia for being ‘so complete’ and hovers, buzzing and glowing, outside their door. Love is usually figured as a woman – Venus or Aphrodite – but this is explicitly a masculine presence. The wings might suggest this is Cupid or Eros, who shoots arrows of desire, but he doesn’t usually cast out a dazzling glare or give out a fearful ‘roar’, and the latter makes Love sound somewhat fiercer than a chubby baby. Here, rather, Love seems to be some terrible, avenging angel. It is surprising and disturbing.

For all this came a ruin: side by side

They were enthroned, in the even tide,

Upon a couch, near to a curtaining

Whose airy texture, from a golden string,

Floated into the room, and let appear

Unveil'd the summer heaven, blue and clear,

Betwixt two marble shafts:—there they reposed,

Where use had made it sweet, with eyelids closed,

Saving a tythe which love still open kept,

That they might see each other while they almost slept

So: here we get an update on what Lycius and Lamia have been doing since we last saw them, and it’s basically bed-rotting. They have a couch near the window, and it fundamentally stinks of sex (‘use had made it sweet’). They’ve just been lying there the whole time either shagging or sleeping. Remember too: they are not married yet.

I’m not fully sure I understand the last image: I think Keats is saying there is something restless about them both in this stage of romance – they can’t ever completely sleep, there’s always a bit of them trying to stay conscious and check the other is still there, a bit like when you’re a new parent and have to check the baby is breathing. (A tithe is a tenth of produce or earnings, that used to be taken as a tax for the church – Love here seems to take a fraction of their rest as his due).

When from the slope side of a suburb hill,

Deafening the swallow's twitter, came a thrill

Of trumpets—Lycius started—the sounds fled,

But left a thought, a buzzing in his head.

For the first time, since first he harbour'd in

That purple-lined palace of sweet sin,

His spirit pass'd beyond its golden bourn

Into the noisy world almost forsworn.

The lady, ever watchful, penetrant,

Saw this with pain, so arguing a want

Of something more, more than her empery

Of joys; and she began to moan and sigh

Because he mused beyond her, knowing well

That but a moment's thought is passion's passing bell.

A trumpet makes Lycius think of the world of men and action again – it is the means by which the outside pierces their bubble. Some archaic words here: I don’t know what ‘penetrant’ means but it seems to contain penitent, and also penetrated – is it a subtle reference to the sex they’ve been having? But it is also their enclosed world that has been penetrated. Also, I don’t know what ‘empery’ means and have failed to find a definition online. Her ‘empire’ of joys? Or I see ‘emprise’ means a chivalrous and daring undertaking (and is close I suppose to enterprise). Maybe that’s in there?

It’s a clearly brilliant last line though– passion is about feeling, and Keats posits that thinking is therefore it’s enemy. We tend to consider both love and rational thought as higher goods. Yet Keats’ is suggesting here that they are mutually exclusive.

"Why do you sigh, fair creature?" whisper'd he:

"Why do you think?" return'd she tenderly:

"You have deserted me—where am I now?

Not in your heart while care weighs on your brow:

No, no, you have dismiss'd me; and I go

From your breast houseless: ay, it must be so."

He answer'd, bending to her open eyes,

Where he was mirror'd small in paradise,

"My silver planet, both of eve and morn!

Why will you plead yourself so sad forlorn,

While I am striving how to fill my heart

With deeper crimson, and a double smart?

How to entangle, trammel up and snare

Your soul in mine, and labyrinth you there

Like the hid scent in an unbudded rose?

Wow! This is an incredibly beautiful passage, and a nuanced, ambiguous description of romantic love. Look how needy and dramatic love makes us! And I adore how Lycius is, in her eyes, ‘mirror’d small in paradise’ – the imagery from Genesis, which was there earlier in the poem, is back. Paradise means a walled garden. But is a walled space also a prison-compound? Romantic love can shrink us: everything reduces to a room, a bed, a person, their smallest gesture or word. And there is a mirror in there again, too – are we only ever really in love with ourselves (in love)? Is romantic love narcissistic?

To love is here to make a heart more bloody; to suffer double pain. It is intensifying. As earlier in the poem, too, there is the imagery of entrapment – of heterosexual monogamous love as a snare. Who wants to be ‘labyrinthed’ after all; lost inside another person’s soul? (Keats is very good – you might have noticed – at repurposing nouns as verbs, which is a technique we might learn from him.) Lycius continues:

"Ay, a sweet kiss—you see your mighty woes.

My thoughts! shall I unveil them? Listen then!

What mortal hath a prize, that other men

May be confounded and abash'd withal,

But lets it sometimes pace abroad majestical,

And triumph, as in thee I should rejoice

Amid the hoarse alarm of Corinth's voice.

Let my foes choke, and my friends shout afar,

While through the thronged streets your bridal car

Wheels round its dazzling spokes."

Lycius wants to show Lamia off, basically. He’s saying that he wants to return to the wider world, but with her, not without her.

The lady's cheek

Trembled; she nothing said, but, pale and meek,

Arose and knelt before him, wept a rain

Of sorrows at his words; at last with pain

Beseeching him, the while his hand she wrung,

To change his purpose. He thereat was stung,

Perverse, with stronger fancy to reclaim

Her wild and timid nature to his aim:

Besides, for all his love, in self despite,

Against his better self, he took delight

Luxurious in her sorrows, soft and new.

His passion, cruel grown, took on a hue

Fierce and sanguineous as 'twas possible

In one whose brow had no dark veins to swell.

Fine was the mitigated fury, like

Apollo's presence when in act to strike

The serpent—Ha, the serpent! certes, she

Was none. She burnt, she lov'd the tyranny,

And, all subdued, consented to the hour

When to the bridal he should lead his paramour.

Lycius doesn’t come well out of this passage: ‘Besides, for all his love, in self despite, / Against his better self, he took delight / Luxurious in her sorrows, soft and new’. But it’s of a piece with Keats’ sense of the cruel dance of heterosexual love. It is all about power – teasing, taunting, conquering, submitting. Lycius finds this power he has over her stimulating. I do find the line about him being ‘sanguinous as twas possible / In one whose brow had no dark veins to swell’ very odd though – sanguinous means both a bloodred colour and bloodthirsty. Sexual desire is perhaps always bloodthirsty to an extent – we want the warm meat of their body. But this image of Lycius turning red with anger and lust seems almost too grim for Keats, he immediately counters it by saying he didn’t actually turn all that red as he hardly has a vein in his brow (???) Does Keats want us to imagine Lycius all swollen and veiny with cruelty or not? If he doesn’t he should maybe stop going on about it…

Lycius is almost godlike in his power over Lamia at this moment. Apollo killed the giant serpent Python in order to establish the oracle at Delphi, so it feels fitting that this image of Lycius’ fury also contains a premonition of snake-like Lamia’s death. ‘She lov’d the tyranny’ is a very powerful line. It reminds me of Sylvia Plath in her famous poem ‘Daddy’ declaring that: ‘Every woman adores a Fascist, / The boot in the face’. That idea women are indoctrinated by the patriarchy to find their own oppression sexy. Lamia cannot help but like it when this man dominates her, even though she senses it will bring about her downfall.

Whispering in midnight silence, said the youth,

"Sure some sweet name thou hast, though, by my truth,

I have not ask'd it, ever thinking thee

Not mortal, but of heavenly progeny,

As still I do. Hast any mortal name,

Fit appellation for this dazzling frame?

Or friends or kinsfolk on the citied earth,

To share our marriage feast and nuptial mirth?"

"I have no friends," said Lamia," no, not one;

My presence in wide Corinth hardly known:

My parents' bones are in their dusty urns

Sepulchred, where no kindled incense burns,

Seeing all their luckless race are dead, save me,

And I neglect the holy rite for thee.

Even as you list invite your many guests;

But if, as now it seems, your vision rests

With any pleasure on me, do not bid

Old Apollonius—from him keep me hid."

Lycius, perplex'd at words so blind and blank,

Made close inquiry; from whose touch she shrank,

Feigning a sleep; and he to the dull shade

Of deep sleep in a moment was betray'd.

Important plot point here: although we have been calling Lamia ‘Lamia’ at Clare’s Poetry Circle as I have found it useful (and her name is in the title of the poem), there is a kind of dramatic irony that has been at play this whole time – we, the readers, have known who Lamia is (and what the name signifies) but Lycius has never once been given this information. He’s literally just proposed to her, and he doesn’t even know what she’s called!! You start to see this guy is completely out of his depth. His excuse is that he doesn’t think of her as mortal, but in part one she told him she was just a local girl from Corinth, so this doesn’t stack up.

Anyway, she also says she doesn’t have a single friend. It is, in the modern parlance, a red flag. As is the fact she doesn’t want Lycius’ tutor and friend, the philosopher Apollonius, to be at the wedding, and when Lycius tries to enquire further she pretends to be asleep. Lots of red flags. Still, Lycius is ploughing on – like someone intent on marrying at a Las Vegas Drive-Thru Chapel before the alcohol wears off, he races away to organise things as quickly as possible. Meanwhile, Lamia too gets ready:

It was the custom then to bring away

The bride from home at blushing shut of day,

Veil'd, in a chariot, heralded along

By strewn flowers, torches, and a marriage song,

With other pageants: but this fair unknown

Had not a friend. So being left alone,

(Lycius was gone to summon all his kin)

And knowing surely she could never win

His foolish heart from its mad pompousness,

She set herself, high-thoughted, how to dress

The misery in fit magnificence.

She did so, but 'tis doubtful how and whence

Came, and who were her subtle servitors.

About the halls, and to and from the doors,

There was a noise of wings, till in short space

The glowing banquet-room shone with wide-arched grace.

This wedding is not being done in customary fashion. It is breaking society’s rules. I love the ‘mad pompousness’ of Lycius’ heart – how absurd, how downright silly, and how vainglorious romance can be! In the meantime Lamia wonders how to dress ‘misery in fit magnificence’. There’s a sort of gloriousness campness to this. She’s a survivor. The show must go on!

And the ‘subtle servitors’ and ‘noise of wings’ are interesting too. Who is helping her? Is it Love, that avenging angel from earlier? Is it demons? Once again, Keats keeps us guessing as to whether her magic is good or ill. She conjures up, not just a dress – like her own fairy godmother – but a hall and a feast. Nothing, however, is solid or substantial. Everything is trembling on the edge of an abyss:

A haunting music, sole perhaps and lone

Supportress of the faery-roof, made moan

Throughout, as fearful the whole charm might fade.

Fresh carved cedar, mimicking a glade

Of palm and plantain, met from either side,

High in the midst, in honour of the bride:

Two palms and then two plantains, and so on,

From either side their stems branch'd one to one

All down the aisled place; and beneath all

There ran a stream of lamps straight on from wall to wall.

So canopied, lay an untasted feast

Teeming with odours. Lamia, regal drest,

Silently paced about, and as she went,

In pale contented sort of discontent,

Mission'd her viewless servants to enrich

The fretted splendour of each nook and niche.

That’s wonderful isn’t it – the ‘fretted splendour’. The over-detailed description conveys her attempt to distract herself with fripperies. She frets over every fret (and threat).

Between the tree-stems, marbled plain at first,

Came jasper pannels; then, anon, there burst

Forth creeping imagery of slighter trees,

And with the larger wove in small intricacies.

Approving all, she faded at self-will,

And shut the chamber up, close, hush'd and still,

Complete and ready for the revels rude,

When dreadful guests would come to spoil her solitude.

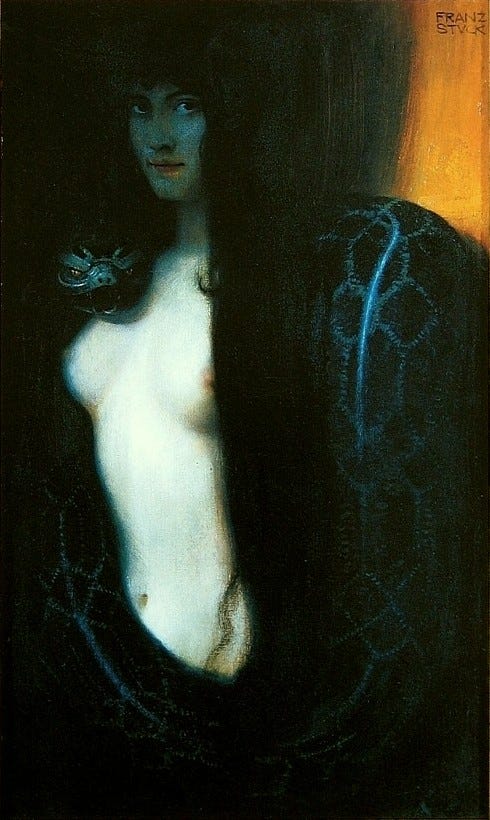

It should be noted that the whole room is like a glade or garden. We spoke in earlier posts about how Lamia is a kind of hybrid of Eve and the serpent, and her eyes have contained ‘paradise’. Now she’s created a kind of walled garden again. But knowledge, in the figure of the teacher Apollonius, is surely going to cause its fall.

We will leave her there – in her hushed, ‘dreadful’ wait – in anticipation of the climax later this week. Thanks again for reading along and do join in and comment!

Super late but I really loved this section!! So many lovely phrases - little bits like "All down the aisled place;" are so appealing and I'm not sure why, maybe having "aisled" as an adjective? Something about the unfloweriness of it too, describing a pretty place without too much telling us that it's pretty - more giving a floorplan of it than trying to convince us.

The pacing from the get-go here also seems more enjoyable and readable, maybe because it's describing what the two characters are doing and how they interact rather than having loads of description of the characters themselves. It's set off so well by the lines: "Why do you sigh, fair creature?" whisper'd he://"Why do you think?" return'd she tenderly.

The 12-syllable lines are a little jarring for me ("And with the larger wove in small intricacies"...//"When dreadful guests would come to spoil her solitude.") - my brain automatically offered the spectacularly ugly (but quite fun) "would come to spoil her 'tude". Maybe it's partly having a line about "intricacies" feeling so clunky? Maybe that's on purpose? Having a line about dreadful guests spoiling solitude awkwardly sticking out feels better though. Not sure if I missed earlier lines that also had 12.

I just read "penetrant" as "penetrating", as in she sees right through to what he's thinking (with possible blue connotations).

Thanks for this analysis!!

I never studied Lamia in depth before so I’m thoroughly enjoying following this series, Clare! ☺️

I love the analysis of ‘the red flags’ 🚩 and how Lycius doesn’t know Lamia’s name, but the reader knows who she is. I think of Shakespeare’s naming of his narrative poem, Lucrece, as just her name - instead of the rape of Lucrece, so to separate her from history constructed by external narratives.

Your poetry stacks are fascinating!! Thank you for sharing xxx